Potash Fertilizer: How to Get the Right Kind of K in Your N-P-K

What is Potash Fertilizer?

Potash fertilizer is fertilizer containing potassium, an essential nutrient for plants. In plants, potassium has an important role in regulating plant growth. Plants use potassium for water uptake and synthesizing plant sugars.

How is Potash Fertilizer Made?

Potash, also called potassium fertilizer, originally got its name from boiling wood and other plant ashes in a pot, which would concentrate the naturally-occurring potassium. Most potassium fertilizers sold today are mined from what used to be prehistoric oceans. Compost, composted manures, wood ash, kelp and green sand also contain potassium.

Benefits of Potash Fertilizer

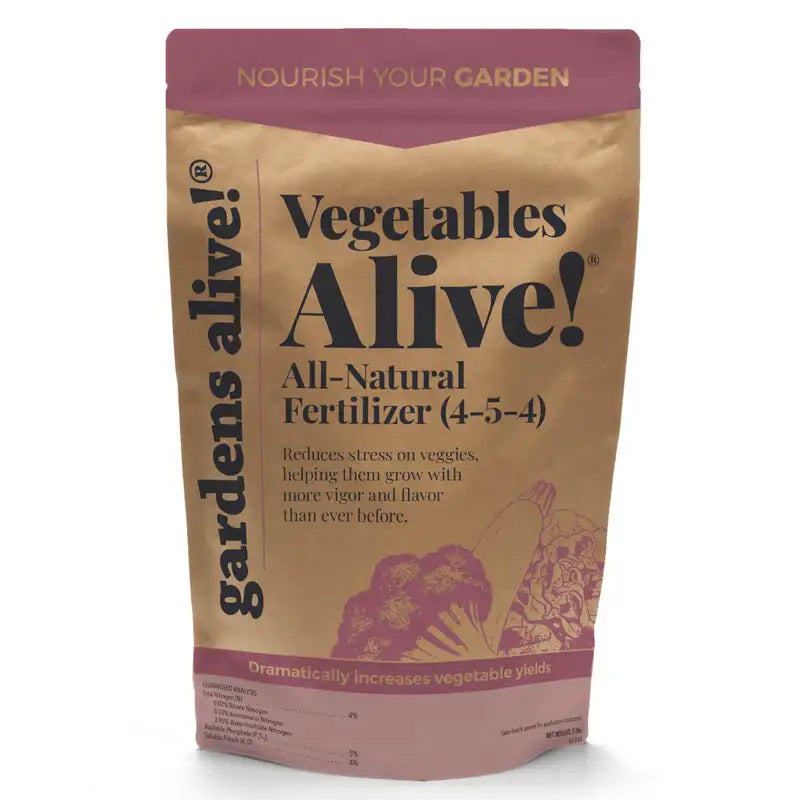

Potash is used to describe any form of potassium that's used in fertilizer. Potassium (K) is a major nutrient and what is listed in the N-P-K ratios on fertilizers (nitrogen-phosphorous-potassium). Potassium aids in a plant's water retention, vigor, yields, nutrient content, color and flavor. Plants take up large quantities of potassium.

Potash Fertilizer Uses

Gardeners use potash to aid in plant growth and bigger fruit and vegetable yields. Before adding potash to your garden, have a soil test conducted. Some soils have sufficient amounts of potassium and require no additional potassium. Also, keep in mind that potash raises the pH of the soil and shouldn't be used on acid-loving plants such as blueberries and hydrangeas.

Other good sources of potassium include wood ash, compost, composted manure, kelp and green sand. Q: Is 'muriate of potash' safe to use as an additive in the raised bed gardens I'll be planting next spring? And if so, do you recommend it? I used it very sparingly along with bone meal and blood meal in an 'in-ground' garden I had in St. Louis, where the clay content of the soil was very high. The garden seemed to have no problem producing tomatoes, cucumbers, < summer squash, and cantaloupe—although the cantaloupe was not very flavorful.I plan on filling my new raised beds with topsoil and my own compost —which started out as a mix of fall leaves and food waste in a tumbler. The beds will be planted with the same kinds of vegetables as in St. Louis. I've purchased the blood meal and bone meal, but none of the garden/hardware/superstores around me carry muriate of potash. An internet search yielded plenty of results, but some sites had warnings that muriate of potash 'is known by the state of California to cause cancer', which led me to seek your advice.

---Jack; "originally from St. Louis but currently residing in Richboro, PA."

A: Centuries ago, true Potash was made by boiling wood and other plant ashes in a pot, which would concentrate the naturally-occurring potassium from the plants into the ashes, hence 'pot-ash': potassium in the form of ashes in a pot. But the term became so popular that, despite being archaic and specific, the word 'potash' is used to describe pretty much any form of potassium that's used as a fertilizer.

(Science Sidetrack: Potassium is the "K" in the 'big three' of N-P-K; the initials used to indicate the relative amounts of the primary plant nutrients Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium on the labels of all commercial fertilizers, whether synthetic, organic or anything in between

Nitrogen (N) grows big plants, but can inhibit flowering and fruiting if used at high levels. Phosphorus (P) is 'the flowering nutrient'; it encourages plants to produce more flowers and fruits—and stronger roots. Potassium (K) pretty much does just about everything else: it increases water retention, vigor, yields, nutrient content, color and flavor.)

Now back to our discussion at hand. Are the words 'potassium' and 'potash' equivalent?

That's almost a religious discussion. Virtually all of the potassium fertilizers sold today are mined from what used to be prehistoric oceans that are now inland, while a true 'potash' would have to have been made from plant ashes. Our listener's "muriate of potash" is technically a contradiction in terms, because it refers to a specific form of potassium—potassium chloride—that's mined (along with salt) from those old oceanic deposits and never saw a pot or ashes. (The word 'muriate' even refers to brine, or salt.) But old-timers love the word, so 'potash' will always be in the N-P-K lexicon.

Now let's cut to the chase and answer the question. Jack is using blood meal to add nitrogen to his garden and bone meal for phosphorus—both are slaughterhouse by-products that some people might oppose ethically but they're about as natural as it gets. "Muriate of potash", aka potassium chloride, is just the opposite; it's a man-made chemical that's generally available in what I consider to be crazy high concentrations. So if he really wants to add the big three individually, I'm going to recommend that he stick to the natural path and look for greensand instead.

New Jersey is the site of the biggest known deposit of greensand—an area that was an ocean shore 80 million or so years ago. The material looks like its name—a green-colored sand. Although the bag will say that it only contains one percent potassium, its actually seven percent. (This form of potassium is released slowly over time, and labeling laws only allow you to use the number that's available to plants the first season.).

Greensand also contains a lot of important and hard to find trace minerals. AND it's said to improve the structure of both clay and sandy soils. But I would be remiss if I didn't add that compost and composted manures naturally contain a good amount of potassium—in a form that should be more immediately available to plants. (Hardwood ashes are also a good source of potassium as long as you confine yourself to small amounts and don't use them anywhere near acid-loving plants like blueberries, azaleas and rhododendrons.)

But even though I have a wood stove (used almost exclusively for fun and power failures) compost is where my garden gets its 'K'. As we always stress, adding two inches of fresh high-quality compost to your beds every season will satisfy all your plants' nutritional needs.

Now, what about this "California Cancer" warning?

Back in 1986, California voters adopted what's known as "Proposition 65" by a wide margin. The Act requires anything that can potentially cause cancer or birth defects to carry the scary warning that you see on a lot of everyday objects. The list is updated every year; and a quick scan of the 800 currently listed chemicals includes a lot of truly bad actors—like arsenic, creosote, the nasty seed treatment captan and virtually every chemical herbicide I've ever heard of.

But I also see the warning on things like clothing and plumbing fixtures. Why?

Two possibilities.

1) The thresholds for getting on the list are very low, and many people do feel that the warnings lack potency because they seem so ubiquitous.

2)Then again, maybe our blithe use of a lot of seemingly harmless everyday objects might explain why we don't seem to be winning the war on cancer.